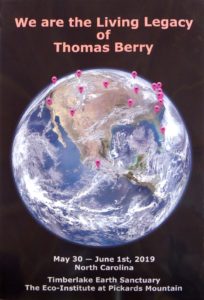

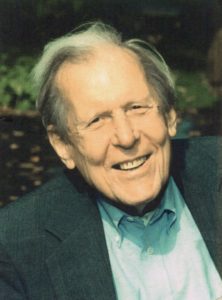

Thomas Berry was a Passionist monk and a passionate lover of the Earth. He called himself a “geologian,” and he tirelessly shared a vision of the sacredness of the universe, the Earth, and the human whose role, he believed, is to participate co-creatively in the magnificent evolutionary process of the cosmos. On this tenth anniversary of his passing some one hundred of us who had been deeply affected by his work gathered together to celebrate the publication of his new biography, share memories of knowing him, describe how his legacy lives on in our work, and receive support for developing our vision for carrying on the task of transforming western culture from anthropocentric to ecocentric.

Thomas Berry was a Passionist monk and a passionate lover of the Earth. He called himself a “geologian,” and he tirelessly shared a vision of the sacredness of the universe, the Earth, and the human whose role, he believed, is to participate co-creatively in the magnificent evolutionary process of the cosmos. On this tenth anniversary of his passing some one hundred of us who had been deeply affected by his work gathered together to celebrate the publication of his new biography, share memories of knowing him, describe how his legacy lives on in our work, and receive support for developing our vision for carrying on the task of transforming western culture from anthropocentric to ecocentric.

On the first day of the conference we met at Timberlake Earth Sanctuary in nearby Greensboro, North Carolina where some 1,800 children a year are given experiences of connecting with the natural world. Thomas was born and spent his formative years in Greensboro and, after teaching throughout the world, returned to Greensboro for the last, very productive, years of his life. He had deeply touched Carolyn Toben who, with his wise counsel, developed Timberlake. We broke into small groups to share the first of several questions that we would discuss throughout the gathering, “How has Thomas Berry touched your life?”

I vividly remember my first encounter with Thomas. In the Spring of 1990 I was struggling to hold together my three passions — for being in nature, for spiritual fellowship, and for creative work. In reading The Dream of the Earth I had been deeply moved by Thomas Berry’s ability to lyrically weave together the material and spiritual dimensions of life with a celebration of human creativity. Moving from the urban Bay Area to rural North Carolina, I had been experiencing many encounters with animals in both the outer wild and the inner wild of dreams and fervently holding the question of what it means when myths and fairy tales and indigenous people all over the world say that animals speak to us. What does it mean that wild animals speak to us?

At the time our son was in middle school. He told us he was writing a book called The Quest. One night he asked me to send him on a quest. I wrote out this Quest for him to take to an Earth Day II school campout:

In polluting the land, air, and waters and in clearing land for development of housing, shopping center, and roads we are destroying the habitats of many species. Without their homes they can’t live. We have lost our ancient deep connection with animals. We regard them only as pets or as food, or as entertaining attractions. That’s why we allow this.

Yet the stories of peoples from all over the world and from all different times tell of communication with wild animals, of animals and people speaking to each other, helping each other in times of need, even of animals being able to transform into people and people into animals. What have we forgotten?

A quest is to find something, an object or an answer to a quest-ion. Your mission, Tristan, should you choose to accept it, is to find out about the native animals who live in your habitat, these Piedmont woods, fields, and streams. And to answer the question: What is communication with animals, and how does it happen?

At the same time there was to be an ecumenical conference on Land Stewardship at Brown’s Summit, where Thomas Berry would speak. I was excited at the opportunity to experience the coming together of spiritual communities in relation to nature. Communities of nature and of spirit were both important to me, but they were rarely joined together. When I arrived I was enjoying a walk in the lush forest amidst wonderful mosses, lichen covered rocks, and wildflowers when suddenly I came upon a very large, lumpy, black rat snake lying right across the path, stopping me in my tracks. A rat snake when confronted kinks itself and becomes motionless. We looked at each other for a long time. I took this as a synchronous appearance. Snakes sense the world around them through picking up vibrations with their entire bodies and tasting the smells in the air by flicking their tongues. This alerted me to tune into my senses and trust my feelings in what was about to unfold.

The presentations were all about stewardship and the ethics and responsibilities of land use. I kept thinking about what I’d overheard a young man say in the morning, that we needed to gain a spiritual relationship with the land, hear the land speaking to us. Yes, I didn’t want to hear about stewardship. I wanted to learn about voice. I wanted to ask the American Indian man sitting nearby what he knew about hearing nature’s voices and to say that this stewardship talk bothered me because it seemed patriarchal. Just then Thomas Berry stood up and said, “It’s not enough to talk about stewardship. We must listen to the voices of the trees, the voices of the animals, the voices of the land.” It was as if he’d heard my thoughts and spoke to me! Ah, here were words that I wanted to listen to!

I went up to him afterwards (wearing my mountain lion earrings for courage) and told him that I had had experiences of plants and trees as a child that I recognized as communication, but not animals. At first he started to talk about having a dog, but I stared him in the eye, and, looking deeply back into my eyes, he said, “You get the communication, you just don’t recognize it. It’s not in the form you expected.” As he spoke I remembered that I had been having these synchronous experiences and dreams of animals. Maybe these were forms of communication — I just wasn’t recognizing them as such. Thus began a life-long exploration of synchronicity and kinship with wild animals and with this man who I felt to be a mentor in such matters. Here at Timberlake many people shared similar experiences of being spoken to very personally by Thomas on a level that deeply supported their unique interests.

Thereafter I heard Thomas Berry speak many times – at Duke, at Carolina, at our local Jung Society, at Earth Spirit Rising, and at many other conferences and gatherings over the years. He continues to speak to me. In preparing for the conference I read an old paper of his, Elders: Their Creative Role in the Human Community, in which he called upon us to take up the role of elders and tell our personal stories of “bio-cultural regionalism” with “a high level of emotional-aesthetic-spiritual communion with the natural world.” These two phrases leaped out at me, his voice loudly supporting what I feel called to convey in my own work as an elder.

I am grateful to Herman Greene of the Center for Ecozoic Studies for reminding us of some of Thomas Berry’s sensual, evocative, love-filled later writings. It is difficult to select out passages as all of his writing is gorgeous, but here are a few to savor: in The Great Work Thomas said, “This we need to know, how to participate creatively in the wildness of the world about us. For it is out of the wild depths of the universe and of our own being that the greater visions must come.” (p.51) “The historic mission of our times is to reinvent the human — at the species level, with critical reflection, within the community of life systems, in a time-developmental context, by means of story, and shared dream experience.”(p.159) He goes on to tell us that in order to create a new ecological civilization, “A new revelatory experience is needed, an experience [in which] human consciousness awakens to the grandeur and sacred quality of the Earth process.”(p.165) “In the end the universe can only be explained in terms of celebration. It is all an exuberant expression of existence itself.” (p.170) To engage in this work we “must feel we are supported by the same power that brought the Earth into being, that power that spun galaxies into space, that lit the sun and brought the moon into its orbit.”(p.174)

Thomas did not mince words. In The Sacred Universe he said, “We are bringing about a devastation of Earth such as the planet has never experienced in the four and a half billion years of its formation. . . We are changing the chemistry of the planet, we are disturbing the biosystems, and we are altering the geological structure and functioning of the planet, all of which took some hundreds of millions and even billions of years to bring into being.” (p.119) He invoked instead a vision of mystical oneness: “The deepest mystery of all this is surely the manner in which these forms of life from the plankton in the sea and the bacteria in the soil to the giant sequoia or to the most massive mammals, are ultimately related to one another in the comprehensive bonding of all the life systems. Genetically speaking every living being is coded not only in regard to its own interior processes but in relation to the entire complex of earthly being.” (p.111) We need a new story, a scientifically informed, functional cosmology: “Spirituality would be understood not as some new piety, rather it would be understood as creative participation in Earth community.” (p.15)

In Evening Thoughts he said, “The universe from the beginning has been a psychic-spiritual as well as a physical-material reality. Within this context the human activates one of the deepest dimensions of the universe and is, thus, integral with the universe from its beginning. . . . Any creative deed at the human level is a continuation of the creativity of the universe.”(p. 57, 59)

On the second and third days of the conference we convened at Pickards Mountain Eco-Institute, meeting in a round red-roofed lakeside gazebo. In small-group circles we again shared our answers to questions such as, “What form is your work taking in the world, and how is it being guided by your relationship with Thomas Berry?” I described the four aspects of the work of Earth Sanctuaries: to tell stories of earth-spirit pilgrimages, to create Temenos Garden Sanctuary, to draw and describe the diverse habitats of plants and animals in our bioregion, and to celebrate life in seasonal ceremonies. But it was later, in conversation with a wise young woman, that I realized that Thomas has become an ancestor of spiritual lineage with whom I can continue to have a relationship, to converse intimately in spirit, asking for his guidance. And, with his love for this land, he is surely an ancestor of Place.

At the end of our time together, as we sat in concentric circles in the gazebo, we were given twenty minutes of silence to reflect on one last question, “What is emergent from this gathering?” Our time had been filled with wonderfully animated human talk. I tend to get lonely when the non-humans are missing. I felt an urge to invite in to our midst some of the critters who had been busy carrying on their lives behind the scenes of our gathering. They spoke this poem to me, and I felt Thomas’s presence again as I stood and read it to the fellowship:

On the Tenth Anniversary of Thomas Berry’s Passing

A swallow sculpts a green smile

of a nest on a beam of the barn above

all our comings and goings.

Cricket frogs shake their marble-

filled rattles louder

than our sweet words of praise.

Tiger swallowtails puddle on the

Tiger swallowtails puddle on the

muddy edge of the lake between

willows and the tag alder, in which

a red-rumped assassin bug lurks,

slurping sustenance, as do we.

Swift swallows swoop over

Swift swallows swoop over

the water nabbing bugs for those

yellow-mouthed babies lined up

at the edge of new life.

Elder flowers, white dinner plate doilies,

Elder flowers, white dinner plate doilies,

hover on the edge of becoming

black-red juiciness.

May we become elders and flowers

and medicine as our Elder

Berry has been for us.

Text and photos (c) 2019 Betty Lou Chaika, except where noted.

Bibliography:

Berry, Thomas. 1988. The Dream of the Earth. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. Reprinted 2015. Berkeley: Counterpoint Press.

—. 1999. The Great Work. New York: Bell Tower.

Berry, Thomas and Tucker, M.E. (eds.). 2006. Evening Thoughts: Reflecting on Earth as a Sacred Community. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. Reprinted 2015 Berkeley: Counterpoint Press.

— and Tucker, M.E. (eds.). 2009. The Sacred Universe: Earth, Spirituality, and Religion in the Twenty-First Century. New York: Columbia University Press.

Greene, Herman. March-April, 2019. “Discoveries Made upon Re-Reading Thomas Berry’s Later Books.” in The Ecozoic Review.

Tucker, M.E., Grim, J., Angyal, A. 2019. Thomas Berry: A Biography. New York: Columbia University Press.

Ellie

Elder Berry! How beautiful. He sounds really special.

Betty Lou Chaika

Hi Ellie, thanks for reading! Yes, it was a sweet synchronicity that the Elders were in full flower on the anniversary of the passing of this man who was such an influential elder in my and many other’s lives. Wish you could have met him.

Blake Tedder

Thank you Betty Lou. I wish Thomas could be part of everyone’s lives here on Earth, as he is part of yours and mine. So very special.

Betty Lou Chaika

Blake, hi! A speaker at the conference reported that someone asked Thomas where he would go when he died. His answer was, “I’ll be in the universe, where I’ve always been.” Such enlightened Ancestors are always close around us, accessible to anyyone who calls to them sweetly.

Sharon Mijares

Lovely and thoughtful tribute to Thomas Berry. Thank you for this.

Betty Lou Chaika

Sharon, you are so welcome. It was a great privilege to have the opportunity to remember Thomas’s influence on my own life and on the life of our community.

Patti rieser

Beautiful reflection, Betty Lou.

Betty Lou Chaika

Patti, how lovely to be in contact with you via Thomas!

Donell Kerns

Betty Lou, thank you for this embracing of the sacred nature of all beings on this beautiful earth. I think and I hope that we are in a turning now to the deeper understanding of our interconnectedness with all beings.

Betty Lou Chaika

Yes, Donell, I agree that the understanding that we are One interwoven Being — people, plants, animals, spirit — is arising from many different wisdom sources. Hopefully, it will enter the mainstream soon and change our behavior towards all our kin so we can honor, protect, communicate with, and be guided by them.

Herman Greene

So well written and insightful Betty Lou.

Herman Greene

Betty Lou Chaika

Thanks for your kind words, Herman, and for all your work through Center for Ecozoic Studies to spread Thomas’s truly profound message that we belong to the Universe physically, emotionally, creatively and spiritually.

Barb

Betty Lou,

I’ve not read Thomas Berry, but how wonderful to learn about him through your words and images! I love the idea that he is in the universe, where he has always been, as you replied to Blake.. And I love the image of swallows in flight sculpting a green smile. I’m wondering how Tristan felt about the quest. I never realized questions are quests.

Betty Lou Chaika

Barb, his book Dream of the Earth is one of my all-time favorite earth-spirituality books for his clarity, open-hearted wisdom and wonderfully poetic writing style. With your love of birds, I’m not surprised that you enjoyed the swallow image! I’ll ask Tristan what he remembers about that Quest. I suspect that you send your grandchildren on similar quests – for knowledge about butterflies, for example, yes?

Margot Ringenburg

Betty Lou, the world desperately needs more people like Thomas Berry–and you! Thank you for continuing to share with others the strong bond that holds you close to the beauty, the wonder, the power of the natural world, through your art, your writing, and the inspiration and solace to be found in your own sheltering and near-magical garden.

Betty Lou Chaika

Margot, thank you for your much appreciated encouragement to continue this outreach. It is good for us all to know that our work of trying to heal our relationship to our beloved Earth matters. Once again I am struck by the beautiful flow of your words, and I look forward to reading more of your writing.

Laurie Lindgren

So eloquent, such a heart-felt song of this human being/bird who is herself an integral part of the Cosmos, part of The Dance!

Betty Lou Chaika

Laurie, I love the image of singing a song to the bird-soul of one who is, indeed, part of the great Cosmic Dance!

Jill Over

Dear Betty Lou,

Thank you for your reflections about Thomas Berry. I have a little story. In the spring of 2002, I had the wonderful opportunity to drive Thomas Berry to the opening of The Universe Story, which was created in the woods (under and between the trees) at the Asheville School in Asheville, NC. Thomas was to be the main speaker and lead us along the path of the creation of the Universe. I had never met him before this. After I climbed the stairs to his small place and knocked, he opened the door, and I immediately connected with him through his smile and soft eyes. He was in no hurry to leave, and, as he made tea for both of us, his first question was, “What are you reading?” As we sat amongst piles and piles of books, we must have talked for an hour. Finally, we got into my Prius, and he expressed amazement at the quiet car! My time with him was precious…only he and I for a few hours! I don’t know if this circular path is still at the school, but I can imagine the spirit of Thomas Berry is somewhere in the trees!

Jill

Betty Lou Chaika

Jill, your act of generosity brought you the great good fortune of spending much intimate time with Thomas. Sounds like he gave you his undivided attention even before you set out on your drive to Ashville, as he has been reported to have done with so many others who met him. His spirit certainly remains with you, and I have no doubt is in the trees themselves as well. He did not keep his soul to himself, he gave himself freely to all levels of Being from the local to the universal.