For many of us the figure of the Cailleach, the crone, has become synonymous with wisdom and autonomous female agency operating outside the oppressive hand of patriarchy. Cailleach, ‘veiled one,’ means a wise or spiritual woman. She has also been called a “hag” or a witch, based on such Old Gaelic terms as cailleach feasa ‘wise woman, fortune-teller’ and cailleach phiseogach ‘sorceress, charm-worker.’ Women with powerful abilities to heal have been termed witches, negatively so by the patriarchy.

There are countless myths and folktales of the Cailleach, she who is the most ancient of the pre-Celtic goddesses of Scotland and Ireland. She is the primordial power of the land itself, deity of the Earth as a living being, as Gaia was for the Greeks. As archetypal mother-goddess, she births life and bestows fertility. As ‘divine hag,’ she represents the dark side of the Mother who brings death (and rebirth). In daily life she takes the form of the local healer, called bean feasa ‘wise woman.’

The Cailleach as Healer

Many Gaelic oral narratives recount cures performed by the local bean feasa through her gifts of prophecy and second-sight.1 Part herbalist, part oracle, she is the representative of the goddess who visits the otherworld to gain insight. As wise woman she diagnoses and heals emotional traumas, both individual and communal. Like shamanic figures the world over, she treats illness by balancing the relationship between humans and the spirits of the otherworld. She restores well-being by restoring her patients’ “harmonious relationships with ancestral otherworld forces.” 2

The Cailleach as Shaper of the Land

Innumerable place-based stories describe her as the personification of the spirit-power of the land itself, as the force of the elements of wind and water (seen most fiercely in winter storms), and as guardian of the plant and animal life-forms.3 On a visit to Ireland, puzzled by my own non-indigenous logic, I asked a guide at Rathcroghan, “How can Queen Maeve be buried here in this mound, inland, when she is also said to be buried in the great cairn on the summit of Knocknarea on the edge of the ocean?” He answered simply, “That means she is everywhere.” The Cailleach, too, is not confined to any one setting, but is the creator of hills, lakes, and islands in many locations. She is, indeed, felt to be “the dynamic, vital force within and across the physical landscape.”4

At Loughcrew, Slieve na Caillaigh, the ‘Hills of the Hag,’ this landscape of hilltop stone cairns is said to have been made by the Cailleach dropping stones from her apron as she bounded across the hills. These Neolithic (3500BC) cairns are burial mounds, but they might also have been sites of ancestor ceremonies. In Ireland, A Sacred Journey Michael Dames suggests that “the apron is the divine womb, translated into the language of dress.”5 Indeed, megalithic burial tombs, with their long passages into interior chambers, such as Loughcrew Cairn T, have been seen by many as symbolic wombs. The imagery is intensified when Cairn T and the great cairn called New Grange at Brú na Bóinne, are penetrated by a shaft of sunlight — at the equinoxes and at winter solstice, respectively.

One of the kerbstones of Cairn T is a massive boulder, 6ft high by 8ft wide, carved with armrests and engraved with ancient symbols. It is called The Hag’s Chair. It faces due north toward the pole star, and traditional tales tell of the Cailleach Garavogue sitting there to watch the movement of the stars. I’ve written about our exploration of Cairn T, and to this day I wonder why I didn’t climb up on the chair and sit with her.

Primal shaper of the land, raiser of the hills themselves, some of the highest, wildest places are named for her. She is the tangible presence of wild nature itself. Her face is seen in the stormiest of headlands, such as on the farthest cliffs of Moher, called Hag’s Head, Ceann na Cailleach. One year, before the park service thought better of it and installed barriers, we hiked the long distance along the cliffs to see her. The path was just inches from the edge of the sheer bluffs, hundreds of feet above the crashing turquoise waves of the wild, deep blue ocean. White seabirds called fulmars would suddenly plane up, eye level, and hang there on the winds created by the intense updrafts generated by the steep cliffs. We were repeatedly startled by the birds’ foraging flights from their nests in the cliff face below. Dizzyingly disoriented, our senses were confused by seeing long-winged birds that should be flying above us cruising over the waters way below. If the awesomeness of the Hag is ever thought to strike fear, for me it was on this hair-raising journey to visit with her.

The Cailleach as Bringer of Weather

The Cailleach, especially in Scotland, represents winter and death, while Brigid represents the creative emergence of spring and healing. The Cailleach’s time is said to begin on the eve of Samhain, October 31st, when she ushers in the dark half of the year. It ends on Imbolc when maiden Brigid brings the beginning of the bright half of the year to all of nature. There are countless stories of the Cailleach’s influence on the weather, but I find this one especially moving:

Once, on a pilgrimage to Scotland, my husband and I hiked through a beautiful dell called Glen Lyon, ‘the valley of Lugh.’ I wanted to experience this landscape in order to feel closer to Lugh, the “god of light.” To better honor him in the Lughnasa ceremonies I had been offering. Had I known that it was also the location of Gleann Cailliche, ‘Glen of the Cailleach,’ with its shrine to her, I would have dragged my poor husband for hours up hills and through deep boglands to find it. At the time, most of the local people had left the area but the setting of the shrine was still kept secret. Recently, however, when a new hydroelectric project was proposed, its location was made public in order to garner support to protect the sanctuary. The scheme was stopped. And the ritual was revived, recognizing that it meets the need for people to fervently honor the Earth now as much, or perhaps even more so, than it did back then.

This shrine is reputed to be the only remaining indigenous shrine of the Cailleach. Tigh nan Cailleach ‘House of the Old Woman’ or Tigh nam Bodach, ‘House of Bodach,’ is a small, turf-roofed stone hut, complete with water-sculpted stone figures. The largest stone represents the Cailleach. The other two are her husband, Bodach, ‘the old man’ and their daughter. Smaller stones may be other children. At the Celtic cross-quarter of Beltane, May 1, the traditional beginning of summer, local families walked to the glen to take the Cailleach’s family outside, where they watched over the cattle and the fertility of the land. At Samhain, the beginning of winter, the people returned and put the Cailleach and her family back inside their hut to spend the winter. Folklorists think this is the oldest surviving indigenous Celtic or even pre-Celtic ritual to her, performed continuously for thousands of years. Each year the local people, and now the new pilgrim-protectors, re-roof the hut with fresh turf in a ceremony of gratitude, in a reciprocity of care, her for them, them for her.

The fragments of legend that remain, as collected by folklorist Ann Ross,6 say that in an unusually strong snow storm, a larger than usual man and woman came down from the surrounding mountains to the upper glen and asked the people living there for shelter. They willingly built a house to fit the supernatural couple. As long as the Cailleach and her family lived on the land, it was fertile and the people were prosperous. One day they told the people they had to leave. They gave stone figures to the people and prophesied that as long as the people cared for them and sheltered them the glen would continue to be fertile. If the people remembered them and looked after their home, they would make sure the winters were mild, the summers were sunny, and the land would remain fertile. In memory of this ancient event the descendants built the small hut and tended the Cailleach and her family.7

The Cailleach as Goddess of Death

In Ireland the great burial mounds such as New Grange and Knowth are the legendary abodes of the mythic kings and queens of the Celtic deities, the Tuatha dé Danaan, the People of the Mother Goddess. These are the Sí, the mounds of the fairy folk. They are portals to the otherworld and entrances to the realm of the ancestors. The Goddess inhabits these abodes of the dead, so they are both tombs of death and wombs of rebirth.

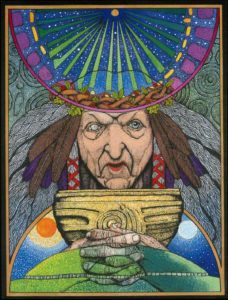

Knowth is Cnocba. In the Dinnshenchas, ‘stories of place,’ of Cnocba, we are told that it is properly called Cnoc Buí, the Hill of Bui. Bui was the mother-goddess of the local peoples. She is the wife of the god Lugh, the omnicompetent king of the Tuatha dé, the very model of kingship. Their marriage, therefore, was one of the sacred marriages of the king to the sovereignty goddess of the land. When Bui died she was buried there, and the great mound was constructed over her body.8 As goddess of this mound of the dead, she is associated with the Cailleach. “The sense of cailleach as ‘supernatural figure, hag-witch’, develops through its association with manifestations in medieval Irish literature of the terrifying, destructive aspect of the sovereignty queen as death-goddess.”9 In the burial chamber of the eastern passage of Knowth there is a large, beautifully carved granite cremation basin. This print of Bui by Courtney Davis that we purchased while we were there shows the cremation basin.

I was not going to mention that the Irish name for owl is cailleach oiche, ‘crone of the night,’ but this morning two pairs of barred owls began calling loudly in the dark before dawn, insisting that I must. Lower female voices and higher male voices kept repeating their long calls back and forth for the better part of an hour. Ascending “Who, who, who, whos,” were followed by what always sounds to me like a warning to be attentive to the Divine: “Who looks for you, who looks for who? Awe.” Periodically they would build to a fever pitch and begin a tumultuous caterwauling of crazy, witchy, yakking and cackling. It seems that the spirits of this land wanted to be heard, too! The respected druid Philip Carr Gomm in The Druid Animal Oracle says, “The Cailleach is the goddess of death, and the owl’s call was often sensed as an omen that someone would die.”

The Cailleach as Goddess of Sovereignty

To earn the legitimate right to rule, Irish kings had to marry the goddess of the territory, the true spirit and power of the land. This was necessary in order to insure the fertility of the earth and, therefore, the health of the people. The marriage of Lugh to Bui is one such bonding. I regard the Bainis Rí, the sacred marriage, as the most important Celtic myth for our times.

My favorite of the ancient sovereignty legends is this: Niall and his four brothers were rivals for the throne of their aging father, King Eochaidh. One day the young men were out hunting. After they had caught some game and eaten it they became quite thirsty. Searching for water, they came upon a well. But the well was guarded by a cailleach, a hideously ugly old hag.10 (In the many recountings of this story, each teller describes her prodigious ugliness in disgusting detail, so fearful it verges on the humorous.)

As each brother, in turn, approaches her asking for water, she demands “a kiss” in exchange. Each brother, repulsed by her scraggly hair and emaciated flesh, refuses her, so his thirst is not slaked. But Niall unhesitatingly embraces her, after which she transforms into the most beautiful young woman of all. She gives him her water and says, “I am the kingdom.” Telling him she is the sovereignty of the land, she bestows upon him the kingship. In this sacred marriage, both are transformed, she from crone to maiden, from winter-barren land to the vibrant new growth of spring11 and he from a mere hunter on the land to the kingly protector of it. This is the reciprocity of giving and receiving. Now, perhaps more than ever, we know that our leaders must care for the health of the earth, so that she, in turn can thrive and give health to the people. The regeneration of life on earth now depends on us. In the age of the Anthropocene, it has become clear that we have altered all of the planet’s life-systems, so it is indeed our responsibility to renew them.

The Cailleach as Ancestor Deity or Deified Ancestor

The Cailleach is claimed as the divine ancestress of numerous tribes. My O’Driscoll ancestors were of the Corcu Luigde tribe. Their descendency is traced back to the divine ancestral mother, Bui, who was married to the god, Lugh, and from whom their name Corcu Luigde is derived.12 Bui comes from Bó, who is the primal goddess of ancient Ireland. Bó is the Old Irish word for cow. So Bó or bui is the sacred cow goddess. The Corcu Luigde were the “Tribe of the Calf Goddess.” Bui is the Cailleach of Beara. The Beara Peninsula was once an important part of the territory of these Milesian Gaels.

According to a compilation of several early medieval texts on the succession of kingship, the present king sees a vision of Lugh. When he enters into the vision, he is brought to the otherworld where he meets a woman who identifies herself as the sovereignty of Ireland. After the woman asks Lugh on whom she should next bestow kinship, she reveals that Lugh has prophesied that Lugaid mac Con of the Corcu Luigde will be the third in a line of kings to receive the hand of sovereignity. Mac Con was indeed a third-century High King. As always, Ireland’s early history is a delightful mixture of visionary legend and semi-historical fact, so I read these tales of my ancestors as inspiring myths more than literal genealogy. These ancestral stories give me a sense of being embedded in the mythic world, even if the kingship descents they describe are not to be taken very literally. But such considerations are not ones to bother the Irish.

The Cailleach as Goddess of Place

There are countless locations in Ireland and Scotland associated with the Cailleach. As Patricia Monaghan puts it in her wonderful book, The Red-Haired Girl from the Bog, “This infinitely divisible goddess lives in those infinitely numerous holy places of the landscape.”13

Indigenous means ‘of a place.’ The indigenous Irish were intimate with the places they lived. One sign of their connection to the land is that every hill and valley and pile of rocks has a name. I remember once looking at a map of a small section of rocky Irish coastline and being amazed to see that every smallest convexity of cliff and concavity of cove is given a name. Another time, looking at a map of pasture lands, I was intrigued to see that every single field has a name. I felt like I was glimpsing a revealed intimacy with the land, an affinity that I could barely imagine, an affectionate familiarity that I was almost ashamed to be witnessing.

Features of the land are often personified by the Cailleach and tales told about her. She is one archetypal Cailleach, but she is many local cailleachs. For me the Beara Peninsula is the Place, and She is the Cailleach Bheara. Seán Ó Duinn calls the whole Beara Peninsula a “ritual landscape.” Legends tell us that it was here that the Milesian Gaels arrived who defeated the Tuatha dé Danaan deities, causing them to withdraw into the saol si, the fairy realm underlying the sacred landscape, the otherworld that is only a hair’s breadth away from this world.

As I write this it is mid-October. I was scheduled to be at a week long retreat on the Cailleach called Reclaiming the Wise Woman with mythologist/psychologist Sharon Blackie. But it was cancelled due to the Covid pandemic. We were to meet at a lovely retreat center located at the gateway to the Beara Peninsula. This is the ancient territory of my ancestors to which my husband and I have pilgrimaged many times. I was excited to anticipate studying the myths of the Cailleach within her landscape. Oh, to have been right there on the land, present with her once again, fervently seeking her wisdom on how we are to move forward towards healing the relationships between our peoples and between humans and the Earth.

The Cailleach: Learning the Myths of the Ancestors

The amazingly rugged, wildly beautiful, and sparsely populated landscape of the Beara Peninsula was once the territory of my Corcu Luigde ancestors. I long to learn their myths and stories. One legend that I am particularly fond of is a story of death and rebirth, of transformation through ritual purification performed by the Cailleach.

The Beara Peninsula is the home of Bui. (Remember, “she is everywhere.”) Bui is the Cailleach Beara, the supernatural shaper of that rocky land. At the western-most end of this peninsula there is a long, even less populated, island called Dursey that stretches out into the ocean. It was originally called Oileán Baoi, the Island of Bui. As we saw, the name Bui is from Boi, from Bó meaning cow. The Cailleach Beara is credited with having formed this large island and the three small islands which lie a little further out in the ocean. These are known as the Bull, the Cow (Inis Buí) and the Calf (Bó Buí). The largest of these, the Bull, is also the legendary Teach Donn, the abode of the dead.

One year, having been charmed by a story that featured these islands, I was determined that our visit to Ireland would include a pilgrimage to see them. Dursey Island can only be reached by a small, rusty, very rickety cable car high above a roiling tidal strait. We were amused to see a scrap of paper with a prayer beseeching safety tacked to the wall of the car. When we disembarked, most of us tourists went to the left. David and I set off to the right, because I had read somewhere that the small rock islands would be best viewed from the right side of the big island.

So we scrambled overland through long, rough grasses and boggy ground, up and down pathless but beautiful hills clothed in purple heather and golden gorse. Finally one, then another island came into view on the right. I felt rather smug. Finally, the third island appeared when we, exhausted, reached the highest point of the island. There we met up with some later cable car riders who cheerily told us about their walk up the smooth road that ran the length of the left side of the island. I guess I must have looked chagrined, because they inquired how we had gotten there. Rather embarrassed, but trying to sound heroic instead, I told them of our difficult overland journey.

An 8th century Irish story called The Expulsion of the Déisi, relates that on a peninsula to the north of Beara, called Dingle, a child was conceived of the union of a local chief and his own sister. As a result of this incest, the crops failed. When the child, Corc, was born, the men of Dingle called for him to be killed, thinking that would remove the shame from the land. A druid, prophesying a great future for the people, offered, instead, to remove Corc from Ireland. He took him to an island called Inis Buí, where he entrusted the child to a cailleach named Bui. For a whole year she washed him each morning on the back of a red-eared white cow. When the year was over, the curse was removed. She turned the cow into a rock in the sea called Bó Buí, the calf of the cow goddess. The shame removed, Corc was now fit to be returned from exile to the company of his community. So, she took him back home to be raised by his grandmother. Free of dishonorable defect, he was made king of the tribe, thus becoming the divine ancestor of the Corcu Duibne tribe of Dingle. The Cailleach Beara is celebrated as their foster-mother.

On first hearing this story I was moved by the abiding compassion of the Cailleach and also of her steadfast cow in bringing healing to the boy. (A red-eared white cow is code for a supernatural cow, an animal-familiar of the divine feminine.) Because a named rock is more perpetual than a fleshly cow, perhaps the cow was thus honored for its service in enduring this daily rite of ablution and in gratitude for taking onto itself the abuse of incest. Because this ritual purification took place near Teach Donn, the House of the Dead, perhaps we can infer that the cow was turned to stone as a sacrificial offering to Donn, God of the Dead. We can witness that this healing required a transformative, initiatory ritual of death and rebirth. Because it is the Cailleach who performs this rite, we are seeing her in her role as goddess of death and rebirth.

Standing on the land, looking out over the place where she healed him, I felt the story coming alive. The islands became animated as the characters. The Cailleach healed me, too. I became connected to my ancestors, to their land, to our land, as I had been never before. I belonged. The goddess, in the form of the Cailleach, became my mother goddess, too.

The Displacement of the Goddess

On one trip to Ireland we visited a certain stone circle. The caretaker, Francie, pointed out magic mushrooms growing in the now largely displaced native grasses at our feet. He told us about the ancient breed of cows that used to roam the hills eating those grasses and the tiny mushrooms that grew in them. He said that when people drank the milk it would induce dreaming. “That’s where the songs and stories came from, and seeing the fairies. But the storytellers are gone,” he said. He waved his arm southward and added, “Maybe you’ll go see the Hag of Beara and have a dream tonight. She was the most powerful woman in Ireland.” The next day we drove south to see her. The large boulder called the Hag of Beara is reputed to be her petrified face. It sits on a hillside above the shore of Coulagh Bay. The local legend is that she was the wife of the god of the sea and the fairy guardian of the otherworld, Manannán Mac Lir. Waiting through seven lifetimes for his return, she finally turned to stone.

The boulder obviously sat on the side of this hill way before the Christian church was built above it on the place called Hag’s Rise. But here begins the local version of the story of the displacement of the divine feminine by the patriarchy. The legend tells us that she regarded the arrival of the saint, for whom the church is named, as a threat to her powers. When she boldly defied him he turned her to stone. Rather than dreaming with her, we were abruptly awakened from the dream of the Earth as a goddess, a sacred being.

The demise of the Cailleach is perhaps nowhere better described than in Irish poetry. The long 9th century Irish-language poem The Lament of the Old Woman of Beare has been celebrated as one of the most poignant and beautiful. It has been translated over and over again. In it Bui mourns her fabled youth, when she was dressed in rich garments and slept with kings, endlessly able to renew her power by natural forces like the tides. Now she is bony and shriveled, fit only to wear the veil of a Christian nun.

It begins: “Is mé Cailleach Bérri, Buí;”

I am Buí, the Old Woman of Beare;

I used to wear a smock that was ever-renewed;

today it has befallen me, by reason of my mean estate,

that I could not have even a cast-off smock to wear. . . .

When my arms are seen,

all bony and thin!

-the craft they used to practice was pleasant:

they used to be about glorious kings. . . .

To have a white veil

on my head causes me no grief;

many coverings of every hue

were on my head as we drank good ale. . . .

I am cold indeed;

every acorn is doomed to decay.

After feasting by bright candles

to be in the darkness of an oratory!

I have had my day with kings,

drinking mead and wine;

now I drink whey-and-water

among shriveled old hags. . . .

It is well for an island of the great sea:

flood comes to it after its ebb;

as for me, I expect

no flood after ebb to come to me.

Today there is scarcely

a dwelling-place I could recognize;

what was in flood

is all ebbing.14

We lament with her that the Cailleach’s tide only ebbs, it no longer flows. We mourn with her the power of divine women reduced to mere nuns serving the god of the patriarchy. We mourn for the land, for each place that was once the dwelling of a goddess.

Mise Éire, “I am Ireland,” is a poem written in the Irish language in 1912 by revolutionary leader and poet Patrick Pearse:

I am Ireland,

Older than the Hag of Beara.

Great my glory,

I who bore brave Cuchulain.

Great my shame,

My own children sold their mother. . . .

I am Ireland,

Lonelier than the Hag of Beara.15

A wonderful poem by contemporary poet Adrienne Rich called Turning the wheel: Particularity, sounds almost like a re-imaging of the Cailleach:

In search of the desert witch, the shamaness

forget the archetypes, forget the dark

and lithic profile, do not scan the clouds

massed on the horizon, violet and green,

for her icon, do not pursue

the ready-made abstraction, do not peer for symbols.

So long as you want her faceless, without smell

or voice, so long as she does not squat

to urinate, or scratch herself, so long

as she does not snore beneath her blanket

or grimace as she grasps the stone-cold

grinding-stone at dawn

so long as she does not have her own peculiar

face, slightly wall-eyed or with a streak

of topaz lightning in the blackness

of one eye, so long as she does not limp

so long as you try to simplify her meaning

so long as she merely symbolizes power

she is kept helpless and conventional

her true power routed backward

into the past, we cannot touch or name her

and, barred from participation by those who need her

she stifles in unspeakable loneliness.16

The stories of Her must not remain in the past, as if she is just part of herstory. As if she is written only in stone. May we envision a time when feminine and masculine modes of consciousness are equally valued as complementary. When there is equality for all shes and hes. May we re-imagine Earth as a living being. Please, may we know once again that Spirit fills the land, that the land is sacred. May we conjure a future in which our relationship with the Earth and her creatures is once again celebrated in stories and honored in ceremonies. May we affectionately attend to the voices of our own inner wildness as we fiercely tend the outer wildness around us to which we belong. That we, that she, might never be lonely again.

Notes

- Ó Crualaoich, Gearóid, “Reading the Bean Feasa,” Folklore, 116, (April 2005): 37-50. Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

- Ó Crualaoich, Gearóid. The Book of the Cailleach: Stories of the Wise-woman Healer. Cork: Cork University Press, 2003.

- Ó Crualaoich, Gearóid, ____

- Ó Crualaoich, Gearóid, ____

- Michael Dames, Ireland: A Sacred Journey, Barnes & Noble, Inc, 2000.

- Ross, Anne, Folklore of the Scottish Highlands, Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd. 2000 p. 114.

- https://cailleachs-herbarium.com/2018/01/the-cailleach-scotlands-midwife-tigh-na-bodach/ and https://www.celticcountries.com/traditions/297-the-shrine-of-the-cailleach-at-glen-lyon

- Tomás O’ Cathasaigh, Knowth – The epynom of Cnogba: http://www.carrowkeel.com/sites/boyne/knowth2a.html

- Ó Crualaoich, Gearóid. The Book of the Cailleach: Stories of the Wise-woman Healer. Cork: Cork University Press, 2003, p 82.

- Ó Duinn, Seán, Where Three Streams Meet: Celtic Spirituality, Dublin: The Columba Press, 2000.

- Ó Duinn, Seán, In Search of the Awesome Mystery: Lore of Megalithic, Celtic and Christian Ireland, Dublin: The Columba Press, 2011.

- Corcu Luigde: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corcu_Lo%C3%ADgde

- Monaghan, Patricia, The Red-Haired Girl From the Bog: The Landscape of Celtic Myth and Spirit, Novato, CA: New World Library, 2003. p. 9.

- Murphy, Gerard. Early Irish Lyrics: Eight to Twelfth Century. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1956.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mise_Éire

- Rich, Adrienne, A Wild Patience Has Taken Me This Far. Poems 1978-1981. W.W. Norton & Co.

Text (c) 2020 Betty Lou Chaika. Photos (c) 2020 Betty Lou and David Chaika, except where otherwise credited.

Bill Murray

Betty Lou,

Very interesting. I especially liked your final paragraph, “May we…”

Bravo.

Bill Murray

Betty Lou Chaika

Hi Bill, thanks for reading and responding. I’m so glad you liked it!

Perry

Dear dear Betty Lou, You keep alive the spirit of Cailleach. More later. Love, Perry

Betty Lou Chaika

It’s a pleasure to share the spirit of the Cailleach with you, dear Perry. Thanks for reading!

Linda McMakin

A wonderful seasonal offering for the Triple Goddess! Bless you and your beautiful work! Love, Amina

Betty Lou Chaika

Amina, I enjoy sharing our love for the Divine Feminine in her various manifestations with you. Blessings on your work for Her, too!

Margot Ringenburg

Betty Lou, yet another impressively-researched and eloquently-written post! The call of the barred owl, whether in broad daylight or the depths of night can’t help but take one to another place and time. So interesting to learn its Irish name: cailleach oiche! During your visit to Dursey, on that absolutely glorious day, you were not merely heroic, but, like the Cailleach, a wise woman to choose the path least traveled. Many thanks for the recommendation of Patricia Monaghan’s The Red-Haired Girl from the Bog. So much to learn from the myths and legends of the ancients.

Betty Lou Chaika

Margot, thanks for your kind words about the story. Ha! I like your interpretation — it being wise to choose the path less traveled! May you get to hike Dursey, too, and I’ll be interested to hear your walking route. Yes, the myths of Ireland and Scotland are fascinating. The connections between the heroes and heroines, gods and goddesses get quite interestingly complicated, don’t they!

ann loomis

Betty Lou, your piece reminded me that when we visited the famous mosque in Turkey, the Hagia Sophia, we learned that “hag” means “holy.” The land is indeed holy, as is the “old woman,” the Cailleach. I was also reminded that The Milky Way is purportedly named for the milk of the sacred cow. It’s helpful for me to imagine the stars of The Milky Way shining and flowing into the land: “On Earth as it is in Heaven.” Thank you for writing this very soulful and informative article!

Betty Lou Chaika

Ann, thanks for your interest. You again prompt me to explore more, this time the Irish word Bó, meaning cow. The goddess Boann’s name (from bó finn) means “White Cow Goddess.” The River Boyne is named for her. One name for the Milky Way is Bealach na Bó Finn meaning “Way of the White Cow.” As you imagine, the Milky Way was seen as a heavenly reflection of the River Boyne. It was sometimes seen as the path of souls.

Laurie Lindgren

I adore this piece, and I am going to be experiencing it daily for a while. I especially LOVE that you have included an original drawing of your own. So powerful! May her voice be heard over the land today, releasing old patterns which have outlived their usefulness, making way for the NEW!

Betty Lou Chaika

Yes, Laurie Hayat, may her wisdom illuminate a path of light through our darkness!

Claire Anderson Graham Kellerman

I learned from 11 years training with Ger Lyons, a Celtic Mystic, who is descended from an unbroken line of healers in Ireland since the beginning of time….the Tuatha were clear that their power in love was so beyond measure, that actually they chose not to fight the Gaels, as it would have been the end of the Gaels.

Instead, the Tuatha chose to live in the mound, below the ground, in the earth; true.

“Defeat” is inaccurate, as I understand our lineage as The Shining Ones, the Tuatha de Danaan.

Aloha, Claire

Betty Lou Chaika

Claire, thank you for your helpful input. Yes, I have no doubt that the Tuatha de Danaan were/are full of wisdom and love. It makes sense that they would choose not to fight, that they would choose to live within the earth.

Kelly Signorini

Thank you for your great insights, it’s great to have a piece written that embraces the Cailleach as she is & not how she was later presented with the patriarchy.

We named our yoga studio after her, Kalyach – as a goddess we can really embrace as our own heritage.