Indigenous Americans for thousands of years have created sanctuaries of earth and sky to commune with Spirit. The Hopewell Earthworks in Ohio are magnificent examples of such holy places. These earthworks form the largest concentration of monumental earthen architecture in the entire world.

The summer after I was bitten by a copperhead we made a pilgrimage to the Great Serpent Mound (c.1000AD) in southern Ohio to make peace with and honor Snake. There we learned of an earlier Native culture, which had flourished nearby—the Hopewell (100BC-500AD), whose amazing artwork and huge geometric earthworks, precisely aligned to astronomical events, formed vast, spiritually-charged ceremonial landscapes—and some of them could still be seen.

We also learned of a wonderful organization called the Arc of Appalachia, which is working vigorously to save precious examples of both vanishing natural ecosystems and ancient cultural sites. When the Arc puts out a new appeal to conserve a new tract of land or an earthwork, the amount of enthusiastic response buoys my hope that people’s love for our Earth will ultimately save us.

This fall, when vaccines allowed safe-enough travel, we made a pilgrimage to see the Hopewell Earthworks. In mid-October we drove from the pines of North Carolina up through the mountains of Virginia and West Virginia, their forested slopes covered with the round green crowns of deciduous trees. Entering southern Ohio, every rural house, it seemed, had their big wide porches and front yards covered with colorful home-made, ghostly, country scenes. Even though it was still two weeks away their enthusiasm for Halloween was infectious.

Most fields were not yet harvested, so cornstalks were standing like ancient dried up persons, adding to the atmosphere of mystery. It turned out, whether fields were cut down or not would largely determine whether we would be able to see the sacred geometries—or not. The evening we arrived in Chillicothe, the geographic center of the Hopewell ceremonial culture, the orange almost-full moon rose over the silhouetted hills of the Logan Range, looking like a string of black Halloween cut-outs. We would not understand the significance of this until later in the trip.

The Ohio Hopewell people constructed many miles of enclosure walls around the earthen circles, squares, and mounds they built for various kinds of ceremonies out of soil they carried in baskets on their backs. The scale of these sites and the work involved is almost incomprehensible. Of some 600 original earthworks, most were leveled by settlers to flatten fields for agriculture and the spread of enterprise.

The small city of Chillicothe has been described as “the ceremonial epicenter of the Hopewell Heartland.” Here, at the confluence of the storied waterways of the Scioto River and Paint Creek, and along their floodplains, some two dozen immense ceremonial earthwork complexes and burial mounds were built. Six of these giant geometric sanctuaries, plus two in Newark, 60 miles north, have been nominated to become a combined UNESCO World Heritage site. Our goal was to visit all of them. The first mystery emerged as we combed through conflicting information on which of them were accessible to the public. We didn’t realize what an adventure, cloaked in intrigue, finding them would be. Having to put in some effort makes us feel like pilgrims rather than mere tourists.

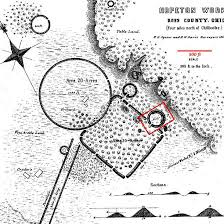

Over the centuries the earthworks were all but forgotten and beginning to fade into oblivion, in memory and to dust, when gradually, beginning in the 1830’s a small succession of individuals began to realize their importance. Finally, two men from Chillicothe, Edwin Davis, a doctor, and Ephraim Squier, a newspaper man, determined to save what was left, if only on paper, and mapped all of them. Squier and Davis, their names legendary, published their beautiful schematic drawings in 1848 in the first publication of the Smithsonian.

Nevertheless, the earthworks continued to be removed, like all the tribes who lived on these lands, to make way for Euro-Americans. Rather recently, various groups of people, like the Ohio History Connection, the Heartlands Conservancy, and the National Park Service, realizing what has been lost, have been banding together to try to bring some of these sacred sites back from the dead. The Arc of Appalachia has made it its mission to conserve both endangered lands and endangered constructed landscapes.

The use of magnetometry, which measures the impact buried features have upon the Earth’s geomagnetic field, is revealing their glorious geometries as ghostly images remaining in the soil under the cornfields. Someone has had a brilliant idea: if the fields are re-planted in native prairie grasses, as these great forest openings would have been when the people built their ceremonial enclosures; and if these miles and miles of newly revealed mound-shadows are mowed precisely, then their shapes can emerge and be walked among once more. It turns out we were there to witness the early labor pains of the re-birth of these glorious ceremonial landscapes.

Junction Earthworks: We literally stumbled upon it. We were driving along looking for another site, when out of the corner of my eye I noticed a sign. This earthwork complex is not one on the World Heritage list, but it is one that the Arc of Appalachia has protected and revealed using the above innovative methods. Formerly a soybean field, now the tall native grasses of the prairie waved in the breeze. Green hills beyond surround the site in beauty. The geometric features were made wonderfully visible by the interpretative mowing and clear signage, so we were able to walk into the series of four large circles, one quatrefoil, three arcs and a square. Standing inside the largest circle, we made offerings and prayers that the US will at last take responsibility and make reparations, taking steps toward a long and honest process of reconciliation between Euro and Native Americans.

The Arc has newly saved a sister site called Steel a bit farther along the clean waters of Paint Creek. Although the site, which has even more earth-forms than Junction, looked amazing on paper, we did not walk the mile to get there, because we were unable to solve the mystery of whether or not it had begun to be interpretatively mowed, thus visible. The Hopewell built their ceremonial geometric structures always in relationship to water, always linking the three worlds—the water world Below, the earth world that emerged from the waters, and the sky world Above. Some works, like Junction and Steel, were constructed on the flat river terraces of creeks, some at the confluence of rivers, and others on flat bluffs above river gorges, these being the shape of the land itself as carved by the waters below. Various aspects of the Hopewell peoples’ mystical relationship to water would be revealed at the World Heritage sites.

First, some of what is known about the people themselves. We don’t know anything about their language or what they called themselves. The people we call the Hopewells were hunters of a great diversity of animals of the air, land, and waters. They were gatherers of the bounty of roots, leaves, nuts and berries from the huge old-growth forests. They tended gardens of cultivated squash and wild plants, like sunflowers, but corn and beans had not yet arrived. Finding food must have taken so little of their time, they had the energy to donate to the construction of their own and their neighbors’ enormous communal earthworks and the crafting of inconceivable amounts of amazing works of ceremonial art.

They were a small population who didn’t live in settled villages. No more than three huts have ever been found together. They lived in small extended-family compounds, scattered around their sacred sites of assembly, never inside them. They lived in peace; archeologists have never found any signs of warfare. No hierarchical structure compelled people to do all this work. Granted, some people were honored by being buried in a special manner, surrounded with beautiful ritual objects, perhaps in gratitude for their shamanic, medicinal, or leadership roles, or for other notable contributions to their community. Otherwise, they were an egalitarian society. No discrimination has been found based on wealth, status, gender, or age. Thus they defied the prevailing analyses of western historians who insisted that ceremonial structures of such scale could only have been built by sedentary agriculturalists living in villages, ruled by an authoritarian hierarchy.

Their population was not large enough to have constructed these earthworks, unless over many generations. The massive amount of work required might have been shared by the pilgrims who came from afar, bringing offerings of precious raw materials from their various regions. They seem to have come together to form their masterpieces out of sheer enthusiasm for their spiritual understandings. Spiritual seekers traveled to these great ceremonial sites in the Ohio River Valley from Native groups encompassing a large swath of eastern North America, to immerse themselves in great world renewal rites, seasonal celebrations, rituals of marriage and mourning.

We know from the offerings they brought that people were drawn here from the Rockies bringing obsidian and grizzly bear teeth; from the Great Lakes bringing copper and silver; from the Gulf of Mexico bringing white shells and the teeth of great white sharks; and from the Southern Appalachians bringing sheets of mica. It’s also possible that youth journeyed afar on personal power quests to obtain sacred materials. The local valued stone was rainbow colored flint from the nearby Flint Hills. Bladelets of this southern Ohio flint have been found throughout these far away regions. It seems that people returned home with these flint bladelets as a form of badge signifying that they had made this pilgrimage and for use in their own ceremonies.

From the artifacts excavated from burial mounds archeologists speculate that ritual dramas to ensure the deceased’s safe passage were performed. Not much is known about how the Hopewell conducted their rituals and celebrations. This is as it should be, remembering that subsequent Native ceremonies were systematically destroyed, not allowed to be practiced again until 1984, and are now guarded and protected. We do know that they highly valued creativity, whether in making sculpted geometries on the land or elegant shapes in stone, or intricate designs cut from copper and mica. Their creativity was in service to, and in concert with, every aspect of the life around them—the rich animal life, the Sun and Moon cycles, the waters, and the interrelationships of these with the people.

To orient ourselves to the locations of the proposed World Heritage sites, we began our exploration at the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park in Chillicothe. The visitor center displayed many of the amazing artifacts that ritual leaders might have worn or the ancestors were buried with, like ear spools and animal headdresses crafted of copper. Thankfully, the excavation, the desecration, of these ancestral burials, which was done in earlier years, would not be done now, out of respect, for which Indigenous peoples have fought. The National Park Service says that tribal nations are consulted regularly about the management of these sites and their preservation. Collaborative research is yielding new insights on the meaning of these sacred sites. While wanting to honor, properly appreciate, and learn from the many artistic forms of their tremendous creativity, I will not further desecrate these ancestors by describing what was found in any specific human burials.

This site in the Park was named Mound City, because within an area larger than ten football fields, 3 foot high walls of mounded earth enclose 23 burial mounds. The green mounds are clearly visible, this being the only site that has been visually restored. As we walked among these huge mounds we made offerings and prayed for the renewed health of and respect for Indigenous cultures, for the return of their lands, and for the just reconciliation of our Euro and Native ancestors.

These mounds were not just piled earth. They were constructed in stages. First a large wooden structure was built upon a clay platform. Fires burned in clay basins. Within, the burials were ritually surrounded by beautiful symbolic artifacts and regalia of gleaming copper and mica. After many such burial ceremonies, perhaps over decades or even centuries, the structure was burned or dismantled, and the entire burial site was carefully covered with succeeding layers of various soils, until a large mound of earth resulted. Even the covering of tombs was a sacred ceremony. The Hopewell ritual relationship to earth through their respectful use of types, even colors, of soil was also to emerge as a theme.

These were shrines of remembrance and healing. Mourners and visitors would have moved among both finished mounds and open buildings within which ritual dramas, perhaps invoking the journey of the afterlife and the balance of cosmic powers, were being enacted. In one double mound there was found a shimmering stack of hundreds of oval sheets of mica. It seems that not only were the deceased honored with mica’s light, but mica itself was honored with a ritual burial of its own

The Mound of the Pipes contained a large bag filled with over 80 beautifully carved animal effigy smoking pipes. Every type of animal from frogs to bobcats, herons to owls is represented. The Park literature said, “All of them had been purposely burned and broken before being buried—probably in a ritual act to release their spiritual power and transport them to the world of the dead.” An effigy platform pipe of a shaman-like figure was studded with white shells. The earliest variety of tobacco, Nicotiana rustica, began to be cultivated 2,000 years ago as a sacred plant used for prayer—at the same time beautiful ritual smoking pipes began to appear in the archeological record. It seems like the effigy pipes were buried as one big smoke-filled prayer for the animals who surrounded their lives. The Arc says, “To our knowledge, no culture anywhere in the world has so prominently paid artistic tribute to the wild animals with whom they shared their world.”

We walked along the trail outside the enclosure walls to the Scioto River, passing some of the large “borrow pits,” which had not only provided earth for walls, but had been carefully lined with clay so they would hold water. The people constantly and wondrously evoked the presence of the three worlds: peering down into these ponds, the water below would have reflected the trees around and the sky above. Standing on a platform above the Scioto we tried to see the prominent hills of the Mt. Logan range. But the still-leafy trees prevented our view.

Here was our first lesson in the Hopewell genius for building their sites not only in reference to the features of their landscape, but also with uncanny astronomical accuracy. The enclosure walls contain two gateways, one in the west and one directly across, facing due east. Imagine this: at summer solstice, we, the people, stand at the western gateway and look across the largest central mound. We see the solstice Sun rise right at the base of the northern end of the Mt. Logan string of hills. At winter solstice we watch the Sun rise at the base of the southern end of these same hills. Equinox sunrises appear right near the peak of the middle pointed hill. The northern and southern minimum moonrises are over the pointed tops of the peaks at both ends of the range. It seems that the land and sky, and the peoples’ propensity to honor them, were made for each other. Their careful observation of the complicated 18.6 year cycle of the Moon was to emerge as another theme.

In addition to Mound City, the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park includes four other World Heritage-nominated sites: the Hopewell Mound Group, Seip, Hopeton, and High Banks. Three other sites that we also hoped to see—Fort Ancient, Newark Circle, and Newark Octagon—complete the list of eight sites on the Heritage application. We were relieved to observe that the protectors of these sites are striving to respect the original peoples and trying to include Indigenous viewpoints in restoring and interpreting them. The park service says, “Many descendants of those forced to move to Oklahoma still consider Ohio [their] homeland and act as stewards to protect the mounds and earthworks here as sacred places.”

The Hopewell Mound Group was the first site that archeologists discovered. It was found on the farm of a Mr. Hopewell, which is how the Hopewell culture acquired its white settler name. It is the largest of the Hopewell enclosures, and here was found the greatest array of exquisite ritual artworks. Over 2 miles of 6 foot high walls enclosed a gigantic area the size of 100 football fields, within which there had been almost 40 mounds covering burial structures, including the largest known Hopewell mound. This triple mound was almost as long as two city blocks and as tall as a three-story building. It is estimated that 1½ million 40-50 lb. basket loads of soil would have been carried to cover the huge three-roomed timber hall, which seems to have been used for various ritual enactments as well as burial ceremonies.

Within this mound was found a cache of nearly 150 obsidian blades and knives and a special placement of dozens of pieces of copper, finely cut into complex abstract designs. Human and animal figures crafted from gleaming mica, like the famous hand and bird claw, accompanied burials, along with lustrous freshwater pearls. The vast quantities of pearls the people collected from the aquatic mussels in their pristine streams and utilized in their ceremonies is testament to how clean the waters were. Mussels help filter and clean rivers. Many species of mussels are now endangered, because they lack the clean water they need to survive. Here was an example of the peoples’ reciprocal relationship with their waters: you grace us with your beauty and life; we honor your gracious bounty by making you into beautiful ritual items.

We stood at a mounted diagram facing the giant field of green before us and were overwhelmed by the immensity of the site. Following a small arrow pointing left, we could faintly see a corner of the giant perfect square that precedes the main, greater enclosure. The square is aligned along its diagonal with the winter solstice sunrise. We could see what remains of the giant mound, but could make no sense of the now-invisible mounds and enclosure walls within the huge open field of rough pasture grass. What a mystery! Perhaps one day this complex center, too, will be re-planted in native grasses, returned to prairie, and mowed interpretatively, although I imagine it is much harder to restore pasture than to restore crop fields.

Now only dimly visible, a large mound near the center of the site called the Flint Mound House covered the remains of a building, at the center of which a giant circular cache of 8,000 flint disks were found ceremonially stacked in two layers on their sides in small bundles. Another mound contained a collection of several hundred pounds of obsidian and foot-long ritual blades. It seems that flint and obsidian were honored as living beings and given their own ritual burials. Perhaps they were gradually placed there as offerings of gratitude by visitors when they arrived for ceremonies. The power of these materials may have been released back to Creator through their burial. I experienced a feeling of deep fulfillment standing upon the earth where such honoring of Earth’s bounty of beautiful stone took place.

We continued on the path up the hillside where it winds through the forest along the well- preserved remains of the high enclosure wall and ditches lined to hold water from nearby springs. Pawpaw trees were turning yellow. Interspersed along the forest trail, patches of lovely prairie recreate a sense of the former forest openings where the peoples’ extended-family homesites, gardens, and hunting grounds might have been found. Nearby, I stood in the riffles of Paint Creek, which is very rich in aquatic wildlife, giving gratitude for its clear waters and sacred mussels and praying that all of our creeks and rivers be restored to health.

It wasn’t until we returned home that I read about the sites’ amazing Great Circle. The earth-shadow of a giant “woodhenge” has recently been discovered there. A huge ring of wooden posts was encircled by an earthen bank and an outer, deep ditch. Four wide gates divide the ring into four quarters, while four communal-sized earth ovens, large enough to prepare great feasts, form a square in the center, one in each quarter of this great circle. The northwestern gate is aligned to the summer solstice Sun as it sets over the nearby hillside. Perhaps one purpose of these feasts would have been to offer praise and gratitude to the power of the Sun.

Archeologists are beginning to call this a world center shrine. Robert Hall described a type of ritual structures found all over the world that he called World Center Shrines, places for prayer to call to the blessings of the Sun, the four quarters of the cosmos, the upper and lower worlds, and to enact rituals of renewal of these powers, in turn to renew the people. In many Native cosmologies we see this iconic division of a circle into four segments radiating from the center, a ritual wheel honoring the four directions of the Creator’s universe, the four seasons, and the sacred cosmic center, the navel-womb of Mother Earth. These contemporary circles are continuous with such ancestral circles, despite centuries of extirpation of much of the oral knowledge of elders and wisdom keepers.

For me, Seip Earthworks is part of a personal mystery: back in 1970 when I was a hand bookbinder I rebound an archeological journal with drawings of five sites, each with a different arrangement of three elements: a large circle, a small circle, and a square. My imagination was quite taken by these geometric earth designs. On the cover I made my own creative arrangement of the elements in colored leather and stampings. The Scioto River Valley lingered as iconic in my mind. In researching the trip I was surprised to recognize these sites in the Squire and Davis drawings and recalled the old book design, which I’d forgotten. I was inordinately grateful, therefore, to be able to see, even to stand in, one of these geometries.

Seip is the best preserved of the five distinctive tri-partite earthwork complexes. An immense circular mounded enclosure is connected to a smaller circle and a huge square with astronomical alignments. Amazingly, each of the elements in all five sites has exactly the same dimensions. Every square, for example, encloses 27 acres. Near the center of the Seip complex, a huge mound, similar in size to the triple mound we saw at the Hopewell Mound Group, has been restored to its former great size. It covered a three-chambered ceremonial hall. Within the hall ancestors were honored with more than a thousand pearls, copper ornaments, bear canine necklaces, and mica cutouts. Here were found preserved remnants of clothing woven of milkweed fibers, dyed to create patterns of circles and arcs similar to the earthworks themselves. People wore on their persons the same symbols with which they clothed the land!

We walked down one side of the interpretatively mowed great square, the length of two football fields, to a platform overlooking Paint Creek. Here we made offerings and prayed for the health of the people, the land and waters, and for the much needed wisdom of the ancestors. I gave gratitude for the mysterious guidance that turns early nascent interests into later fulfillments.

Being so surrounded with mystery, we almost didn’t go to Hopeton Earthworks. Brochures said it wasn’t open to the public. A ranger said it was, but that it had been hayed, so we probably wouldn’t be able to see anything. We decided to give it a try, anyway. Hiking in, we were pleased to see that colorful wildflowers still graced a restored prairie. These ceremonial grounds were used in conjunction with the burial site, Mound City, directly across the Scioto River. Low parallel walls of earth, nearly a half mile long, once led up from the river to the joined enclosures in the shape of a gigantic square and circle. The avenue aligns with the summer solstice sunset.

The walls of the square enclosure were once 12 feet tall and 50 feet wide. The square and two small circular enclosures were interpretatively mowed, so the wide walls of these earth forms were now revealed, covered in wildflowers. They were impressive to see and lovely to walk among. Only the Great Circle was hayed and hard to detect. It is 1054 feet in diameter, the exact dimension of the circles at four other earthwork sites. Even their units of measure had sacred meaning.

The walls of the enclosures were made of carefully arranged layers of different soil types. Reddish clay was used on the exterior of the walls and yellow clay on the interior. Standing inside, with the sun shining, celebrants must have seemed surrounded by gold.

In addition to the ceremonial grounds made on the river terraces, the Hopewell people also created ceremonial landscapes by mounding walls of earth or stone along the perimeters of high plateaus above river gorges. Settlers thought these must be defensive forts, although they are obviously not, but the name stuck. There are a dozen hilltop enclosures in southern Ohio, nine of which are now conserved. Fort Ancient is the largest of these and the best preserved.

At Fort Ancient three-and-a-half miles of undulating earthen walls, varying in height from 3 to 23 feet, follow the contours of the entire bluff, forming North and South “forts” overlooking the Little Miami River. The walls contain over 60 openings, or gateways. Paralleling the inside of the walls, a necklace of clay-lined ponds reflect the earth walls and sky above. The people intentionally joined the two natural watercourses below to surround the earthwork with water, as if to simulate the Earth emerging from the primordial waters below, as so many Native creation stories tell.

We entered the North Fort through a high pair of mounds. There, four stone calendar mounds form a square, about 525 feet on a side, half the ceremonial circles’ 1054 foot dimension, marking this square as sacred and linking it to the cosmos. The north mound aligns with a gateway through which winter solstice sunrises were celebrated. Standing at the south mound, people viewed the summer solstice sunrise and the maximum and minimum northern moonrises through three gateways in the tallest enclosure wall.

Near this mound, research has revealed the remains of a woodhenge that consisted of three concentric rings of large posts. The outermost circle was about 200 feet in diameter. At the center of the circle, the Hopewell built a wide, shallow basin that they lined with bright orange-red burnt soil—perhaps as an altar. This circle was the heart of the whole ceremonial site. The altar aligns with the south stone mound and the gateway through which the summer solstice Sun rises. After their last ceremony they ritually removed the wooden posts and buried the circle under layers of gravel hauled 250 feet up from the bed of the river below. Everything these ancestral people did was done ritually, as is the Native practice now. Standing between the circle and south mound we made prayers of gratitude for all people who honor Earth and Cosmos in sacred ways and for those who are working tirelessly to preserve and maintain these ritual sites.

The gorges narrow the plateau between the North and South Forts, where the sculpted walls draw close on both sides. Two crescent mounds mark a ceremonial pathway. Then the passage grows even narrower, passing between two high mounds. As we walked, imagining ourselves part of the pilgrimages that took place here, a huge feast of shagbark hickory nuts and white oak acorns was taking place.

Back at the North Fort we viewed exhibits in the museum that illustrate what is known of the history of the Native peoples of Ohio from their arrival after the last glaciers retreated (15,000 years ago), through the many broken treaties that shrank their lands, to the final tragic Indian Removal. No tribal nations are recognized as living in Ohio now. While appreciating the respectful revealing of their ancestral culture, Shawnee, Miami, Delaware, Ottawa and other descendants understandably express conflicting feelings about viewing the sacred burial artifacts in the museum.

It finally became clear that we wouldn’t be able to get to High Banks at the confluence of the Scioto and Paint Creek, because it is only open to researchers. The High Banks earthwork site is one of only two that have an octagonal enclosure. The other is Newark Octagon sixty miles away. As at Newark, the High Banks octagon is attached to a circular enclosure by a narrow opening. The diameter of these enormous circles at High Banks and at Newark is the same sacred dimension, 1054 feet. They both align to the once-in-a generation maximum northern moonrise, as well as to the places on the horizon where the other key points of the Moon’s complicated 18.6 year cycle of risings and settings appear.

Even though Newark is so far north of the heart of the flourishing Hopewell culture at Chillicothe, it was very much a vital part of the same vast ceremonial landscape. Built at the confluence of two rivers, Newark Earthworks was by far the largest and most complex marvel of Hopewell engineering ever, itself encompassing over 4.5 square miles. Most of the enigmatic arrangements of earthen ceremonial works were obliterated by the growing city. But, through dedicated efforts, two main elements were saved, the huge Great Circle (bottom) and the Circle-Octagon (upper left).

Whether or not we would be able to see these was the greatest mystery of the trip. We were confounded by much conflicting information, but in the end decided to give it a try. We arrived to find the small museum closed, but the Great Circle open to the public. We passed through the magnificent ceremonial gateway, the massive 14 foot walls towering above us, at the base of which a deep, wide ditch, lined with clay and stone to hold water, ran along the entire interior of the circle. Here, as at Hopeton, the circle’s enclosure walls were made brownish red on the outside and golden facing the celebrants. We could barely make out the walls on the other side of the circle, four football fields away, and were overwhelmed by its incomprehensible size.

We drove to the Newark Octagon, which is the Moundbuilders Country Club. Sad morphed to glad when we found out that this is actually how the Octagon was saved. But it’s also why it’s not open to the public, except four days a year. The day before we left for Ohio was one of them. We climbed the wooden visitors’ platform from which we had a clear view of the parallel-walled avenue between the awe-inspiring circle and octagon.

We kept seeing hawks and what looked like small falcons repeatedly flying between tall trees, raising clouds of jays and other birds. As we walked along the enclosure walls of the circle we discovered why. Huge old beech trees were dropping millions of beechnuts that crunched under our feet. We continued along the circle, looking into the bizarre golf course, until we got as close as allowed to the Platform Mound. Standing on this mound, once in a generation, people could see straight through the circle, through the avenue, and through the Octagon’s farthest gate to the full Moon rising at its northernmost point. This is Lunistice, the time of the northern lunar standstill. Perhaps this is the greatest example of how the Hopewell intimately connected themselves and their earthly ritual sites to the heavens; how they linked the cycles of their ceremonies to the rhythmic cycles of the cosmos. Here’s an interpretation of how that would have looked:

We walked the Octagon, seeing how its walls form gates at each of the eight corners, with a mound inside each entrance, to the earthen mounds that form the beginning of the Great Hopewell Road. This 200 foot wide avenue has been traced for 6 miles, before disappearing in woods and swamps. It points straight to Chillicothe. Brad Lepper, the curator of archeology at the Ohio History Connection, thinks it was “a sacred processional path used by pilgrims to travel to Newark’s gigantic earthen cathedral.”

What happened to the Hopewell? There is no evidence of warfare or signs of any cause of dispersal. The most convincing explanation, Lepper’s, is that they simply could not sustain this great explosion of artistic and spiritual flourishing beyond 600 years. The NPS says, “The monumental architecture and artifacts of the Hopewell culture reflect a pinnacle of achievement in the fields of art, astronomy, mathematics, geometry and engineering.”

Each of these eight Hopewell Earthworks, (and Serpent Mound) meet UNESCO World Heritage site criteria as a “masterpiece of human creative genius” and “outstanding universal value.” Once the legal issues involving the golf course are resolved, it is hoped that World Heritage status will be granted.

I am grateful for these ancestors who saw the Earth as one big ceremonial landscape; who joined their spiritual journey intimately with that of the Sun and Moon; who honored the waters Below as equally sacred to the sky Above; who deeply revered their animal kin and the sacred materials of earth—the soils, the stones, the minerals—with which they made their inner awe visible in masterpieces of architecture and artistry and who practiced reciprocity with everything in their world.

On our way back south, the color change through the mountains was dramatic and brilliant. Like colorful flags waved by crowds of jubilants, the trees echoed our elation at the magnificence we had experienced. Shortly after our return I woke over and over again with a repeated vision: I’m looking straight down upon land bordered and shaped by a confluence of rivers. Large, round seeds are raining down, keep raining down, upon the land.

Waking with this image of sacred land, water, and sky filling my mind, I realized it was a composite image of the two types of ceremonial sites, those at the confluence of rivers on flat terraces below and those at the confluence of rivers on plateaus above. The dream-maker knew the geometric sites and the “fort” sites were symbolically the same. Sites of extreme sacredness, seeds, like offerings, are raining down upon them.

I’m grateful for all the people who are partnering to help seed the vision of these earthworks as alive and sprouting back up from the Earth. May the visionary seeds planted by native and non-native people continue to germinate and grow into vast conserved lands that will help us to perceive and receive the wisdom the Great Mystery. May the seeds of reverence planted by ancestors, who held these and other motherlands sacred, flower and assist us in recreating a vision of the sanctity of land, water, and sky wherever we live.

Text (C) 2021 Betty Lou Chaika

Notes:

*CERHAS is the Center for the Electronic Reconstruction of Historical and Archaeological Sites

**Hively, R. and Horn, R., Hopewell Cosmography at Newark and Chillicothe, Ohio, 2010, University Press of Florida. In this publication the authors make a very detailed analysis showing that the Hopewell astronomical observations were aligned with the features of their natural landscape.

I’m indebted for the information in the article to the various brochures provided by the Ohio History Connection, the Heartlands Conservancy, Arc of Appalachia, and the National Park Service, as well as to various local newspaper articles such as those by Brad Lepper in the Newark Advocate, and the UNESCO application.

For further reading I would recommend the “Hopewell Ceremonial Group Justification for Inscription,” prepared by Bret J. Ruby, PhD, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, and Bradley T. Lepper, PhD, Ohio Historical Society, as part of the UNESCO World Heritage application. In it the Hopewell sites are fascinatingly compared to ceremonial sites all over the world.

Karen Rossie

Thank you for this loving, important, and carefully respectful description and for sharing it through the story of your experience. What a gift this is and how perfect to read on Thanksgiving!

Betty Lou Chaika

Karen, thanks so much for letting me share with you the story of this wonderful Hopewell culture’s wholeistic vision of Earth-Human-Spirit.

Ann Gayek

So much I didn’t know! Thank you for your thorough explanations, the research, the photos. This took some time to put together! And I’m glad you were able to visit so many of these sites.

Betty Lou Chaika

Thanks for reading, Ann. I hope you get to experience these earthworks again as they are being made more and more visible. Perhaps gaining World Heritage recognition, as is hoped, will provide the energy, support, and momentum to carry on the work of making them accessible to be walked among once more.

Forest

Epic and soul-stirring. Mid-reading I veered off into searches of some of Chillicothe’s history and so much else of which I was unaware, link after link. Thanks for revealing to me the existence of the Historical Park!

Betty Lou Chaika

Forest, so glad you read and were stirred! Here is the ending I was inspired to add for the version that will appear in the Book:

“Another vision arises: World Heritage status is granted. The Hopewell peoples’ understanding of Earth and Sky, humans and non-humans, as one sacred ceremonial community is made visible in its entirety, and is recognized as an enormous World Center Shrine. In a ceremony our Native kin are finally and fully honored as those who have known all along how to honor Mother Earth and are given vast homelands to manage as their own. We Euros who have fancied ourselves as the true owners of the land come here to humble ourselves, beseeching to be taught how to live on this blessed earth, respectful of her gifts. Pilgrims come from afar to experience this magnificence, to be reminded how their own ancestors lived, and how the Indigenous people of their own lands still live, as co-creators with the benevolent Mystery of an earth-honoring life filled with beauty and love.”

Margot Ringenburg

Betty Lou, I am so thankful for FINALLY finding a block of time to read the tale of your journey back to the time of the Hopewell people, with its focus on their magnificent earthworks, as well as their “artistic tributes” to the natural world that surrounded them and infused their culture. Many years ago, Dave and I drove to Fort Ancient, with Ali & her good friend Crissy in tow. A thought bubble was in plain sight above their heads: “Only the weird Ringenburgs would spend the 4th of July at a place like this.” Fortunately, they were too polite to voice this complaint out loud. There is no better time than autumn to travel across the Blue Ridge and Ohio Valley into southern Ohio and the Hopewell peoples’ “sanctuaries to earth & sky.”

Betty Lou Chaika

Yes, Margot, I imagine that Fort Ancient would be a strange place to spend one’s 4th of July! Oh, but I hope the “weird Ringenburgs” get to see the other Hopewell Earthworks as they are re-emerging into visibility. I wonder if you have hiked any of the Arc of Appalachia’s trails. I long to see some of the wet and dry prairies above Serpent Mound. Southern Ohio is becoming one of my favorite landscapes!

Barb Stenross

As a college student, I lived not so far from these amazing spirit- and art-works, but never visited them. Thank you for the chance to appreciate them through your travelogue and sensitive reporting. I am greatly saddened that the indigenous peoples of Ohio were displaced by European-Americans who had so little understanding of and respect for, these deeply spiritual, brilliant cultures. The animal pipes are incredible. As a child in Cleveland, Ohio. I was once struck by the feeling that one area in my neighborhood, not too far from Lake Erie, had been a Native burial ground. I have no idea how this thought came to me, but I always walked in that area with a feeling of reverence. Thank you, Betty Lou.

Betty Lou Chaika

Barb, I hope someday you will get to see them on a trip up to Ohio. And when your grandsons are older. . .As a spiritually sensitive child you knew what we all should know–that Native people are buried beneath our feet, and the earth is to be walked upon with reverence.